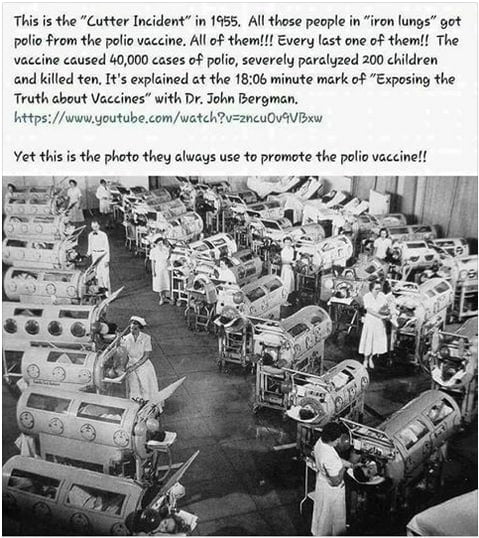

In April 1955 more than 200 000 children in five Western and mid-Western USA states received a polio vaccine in which the process of inactivating the live virus proved to be defective. Within days there were reports of paralysis and within a month the first mass vaccination programme against polio had to be abandoned. Subsequent investigations revealed that the vaccine, manufactured by the California-based family firm of Cutter Laboratories, had caused 40 000 cases of polio, leaving 200 children with varying degrees of paralysis and killing 10. It’s explained at the 18:06 minute mark of “Exposing the Truth about Vaccines” with Dr. John Bergman.

Exposing The Truth About Vaccines

These Materials below from this website, Get More photos and related history on Polio and Vaccines here https://amhistory.si.edu/polio/index.htm

| Introduction Every photograph is both truthful and deceptive. Every photograph is edited by the photographer. Each photograph is taken for some purpose, and that purpose determines what is shown and how it is shown (by the selection of such things as camera angle, framing, and composition). As time passes, it becomes difficult to retrieve the photographer’s intent as well as the way in which people of another era would have viewed and understood an image. We must rely on historical knowledge to see through a photograph to the evidence it reveals. These images were selected to illustrate some of the intricacies in reading historical photographs. |

| Historical Photo 1 |

|

Courtesy of Polio Canada/Ontario March of Dimes

| In this staged photograph, a nurse shows a newspaper with a headline about the polio vaccine to a man using a chest respirator. There is an element of cruel insensitivity in what is taking place. The nurse seems oblivious to the psychological impact of the headline on this man who was unable to benefit from the vaccine. But in the context of 1955, this image captures the intensity of the relief that people felt when an effective vaccine was found. For the nurse and many others, elation over the existence of an effective vaccine trumped every other emotion. |

Left: March of Dimes poster child

Right: Hallmark card, with their focus on children, 1950s

| The image on the left functions as a kind of community-based propaganda to motivate people to act. It is rooted in the baby boom years of the 1940s and 1950s, with their focus on children. Sweet, sentimental images of childhood appeared on greeting cards and advertising throughout the decades. |

| Historical Photo 4 |

|

Iron lungs in gym Courtesy of Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center

| At first glance, this image shocks and saddens from the enormity of the problem of sick children in need of iron lungs. On closer examination, it is clear that the equipment that usually accompanied people using iron lungs, such as tracheotomy tubes and pumps and tankside tables, is not present (compare the picture to photographs in the section on the iron lung). This scene was staged for a film. It is not historically accurate as a respirator ward, but is an example of an established photographic technique (famously used, for example, by WPA photographers in the 1930s) of directing the viewer’s response by creating a shot that would not naturally occur. |

| Historical Photo 5 |

|

Young girl wearing only a diaper

| In this image, taken from a 1917 medical textbook, the access point is that of the medical professional. The physician is in control of the anonymous “polio case.” Visual inspection of patients, as illustrated here, was a critical part of medical education. The patient’s context is missing because it was not important for the image’s intended audience. Consequently, the photograph captures assumptions about the doctor-patient relationship, power, and the vulnerability of those who are ill. |

| “‘He’s pretty lightweight for a ten year old, isn’t he ma’am?… I’ll carry the boy down the steps if you can manage your bags.’ It began then, the feeling of being treated like a thing.” —Don Kirkendall, 1973 “Medical student without consultation pulls down the sheet over naked me. I don’t even know him and he is undressing me without my specific permission. I am wracked, and yet I remember thinking, ‘I don’t want them looking at me without my clothes, not at all’ But no one is listening to me. My body is no longer my own.” —Lorenzo Wilson Milam, 1984 |

| Historical Photo 6 |

|

Informal birthday party Courtesy of Laura Kreiss

| Snapshots and informal photographs have an altogether different composition. This amateur shot was intended for use as a memory aid, not for any didactic purpose. The composition is quick and chaotic, reflecting the bustling activity of the party. It captures the central figure, along with his birthday cake, but cuts off others at the party as well as details of the room. Yet at the same same time, unlike the medical image, it grounds the subject in his social relationships, rather than presenting him as an isolated individual. |

From Rehabilitation Gazette, motorcycling

Left: Race with tank

Right: Lorenzo

Left: Trick-or-treating, Halloween kids with mom

Right: Adele and Chuck Mockbbee

| Photographs courtesy of Post-Polio Health International, Dan and Carol Wilson, Yoshiko Dart, Lorenzo Milam, Laura Nell Obaugh and Felix Oppenheim-Wedgewood, Joy Weeber and Ron Mace, Laura Kreiss and Ben Minowitz, Marc Shell, John Britt, Jack Warner, Richard J. Castiello, Dick and Barbara Eckhardt, Jean-Marc Giboux, and Rotary International |

|

Left: Laura Nell Obaugh and Felix Oppenheim Wedgewood in England

Right: Ed Roberts and son

| “Polios have a certain advantage over the able-bodied when it comes to aging…. We do not confuse the quality of our life with the quality of our tennis game. We know that happiness is not dependent upon activity nor is meaningful defined by trophies. A meaningful life may be hampered—but need not be defined—by pain or disability.” —Hugh G. Gallagher, 1998 |

Young people who experienced post-polio syndrome

Left: Jim Morse with his short wave radio equipment

Right: From Rehabilitation Gazette, mother with kids at playground

| “While polio is a physical experience, it is also a social one…. Polio does not belong just to those of us who were infected by it, but to our mothers and fathers, our sisters and brothers, our partners and our children; to those who cared for us, to those who brutalized us (often not mutually exclusive categories); to those who saw us as palimpsests [tablets] on which to write their fear, their pity, their admiration, their empathy, their discomfort.” —Anne Finger, 2004 |

Joy with her family, Christmas

Left: Dick and Barbara Eckhardt’s wedding

Right: John Britt’s wedding

| Photographs courtesy of Post-Polio Health International, Dan and Carol Wilson, Yoshiko Dart, Lorenzo Milam, Laura Nell Obaugh and Felix Oppenheim-Wedgewood, Joy Weeber and Ron Mace, Laura Kreiss and Ben Minowitz, Marc Shell, John Britt, Jack Warner, Richard J. Castiello, Dick and Barbara Eckhardt, Jean-Marc Giboux, and Rotary International |

| “I don’t think that my disability really changed anything as far as my relationship with my wife and children…. [When] our daughter Louisie was in school (she must’ve been really little), the teacher said to her, ‘Your dad is Bob Gurney. He’s the one who is handicapped.’ Well, Louisie told her, ‘No he’s not. He’s my daddy!’” —Robert Gurney, 1996 |

Left: From Rehabilitation Gazette, party and presents

Right: Party time

Newsletter mailing picnic for the Gazette, 1959

| “‘What happened to your leg?’ he asks me as he’s loading the groceries into the trunk of my Volvo. ‘I had polio.’ ‘What’s that?’ I feel like an aging movie star who’s been asked her name by a restaurant maitre d’. Polio was as famous as AIDS. Those of us who had it were figures.” —Anne Finger, 2004 |

Left: Dick Anton out fishing

Right: Joan Sands and her family