Systematic reviews are now more important than ever

By Dr Tess Lawrie, MBBCh, PhD

Bringing the Together trial data together with the rest!

I want to talk to you today about the Together trial on ivermectin as a treatment for Covid-19. There is a lot of discussion about the quality of the data and the conclusions drawn in this trial – but there is an equally, if not more, important point to consider.

Whenever new trial data comes along, as with the Together trial, it is essential to put it in context. That is, it must be evaluated in relation to all the relevant and reliable evidence available.

This is done by conducting a systematic review. Systematic reviews are useful because they give you the big picture, the bird’s eye view. They do this by pooling the data from different studies done by different research groups all trying to answer the same questions. Presented as forest plots, pooled data analysis called meta-analysis is the main focus of systematic reviews.

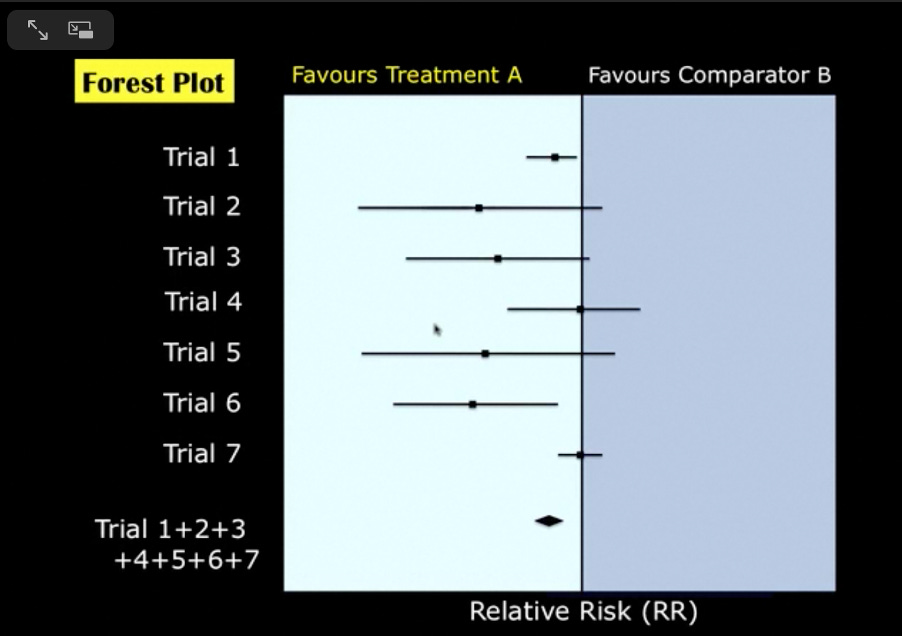

Let me show you an example of a forest plot:

Here you can see there are seven trials, and the diamond shape at the bottom represents a summary effect estimate (relative risk) of the data from these trials. Because the diamond shape is clearly to the left of the vertical line, the evidence in this forest plot favours Treatment A.

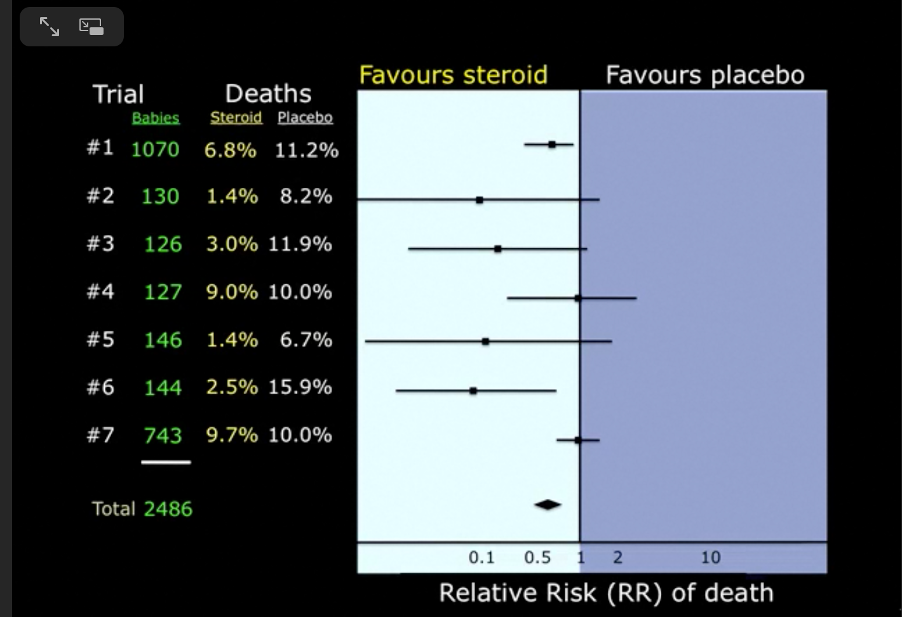

This particular forest plot was derived from a systematic review that asked the question: Do maternal corticosteroids versus no corticosteroids for preterm birth prevent newborn deaths?

Approximately half of the babies’ mothers were given corticosteroids, the other half were not. By 1981 the total number of women enrolled in these trials was 2486 and the overall effect showed a clear benefit in favour of corticosteroids, yet the evidence from these small trials was not trusted. It took a decade and another ten trials to change medical practice and, as a result, many small babies must have died unnecessarily in those ten years because their mothers did not receive corticosteroids.

Cochrane, the organisation behind the Cochrane Library database of systematic reviews, said “This delay was terrible because it meant that babies were denied effective treatment because it took so long to act on evidence accumulated in randomised trials.”

This forest plot actually became the logo for Cochrane – as you can see here.

The original Cochrane logo serves as a reminder of the importance of small trial data, as delays in waiting for large trials to be done may be associated with unnecessary loss and suffering. On a more general note, I would say it reminds all of us of the value of systematic reviews and meta-analysis in identifying effective treatment.

So, how does all this relate to the Together trial and ivermectin? Well, let’s take a look. Remember that a systematic review looks at all available and reliable evidence so that we can gain an understanding of whether a particular treatment is effective or not.

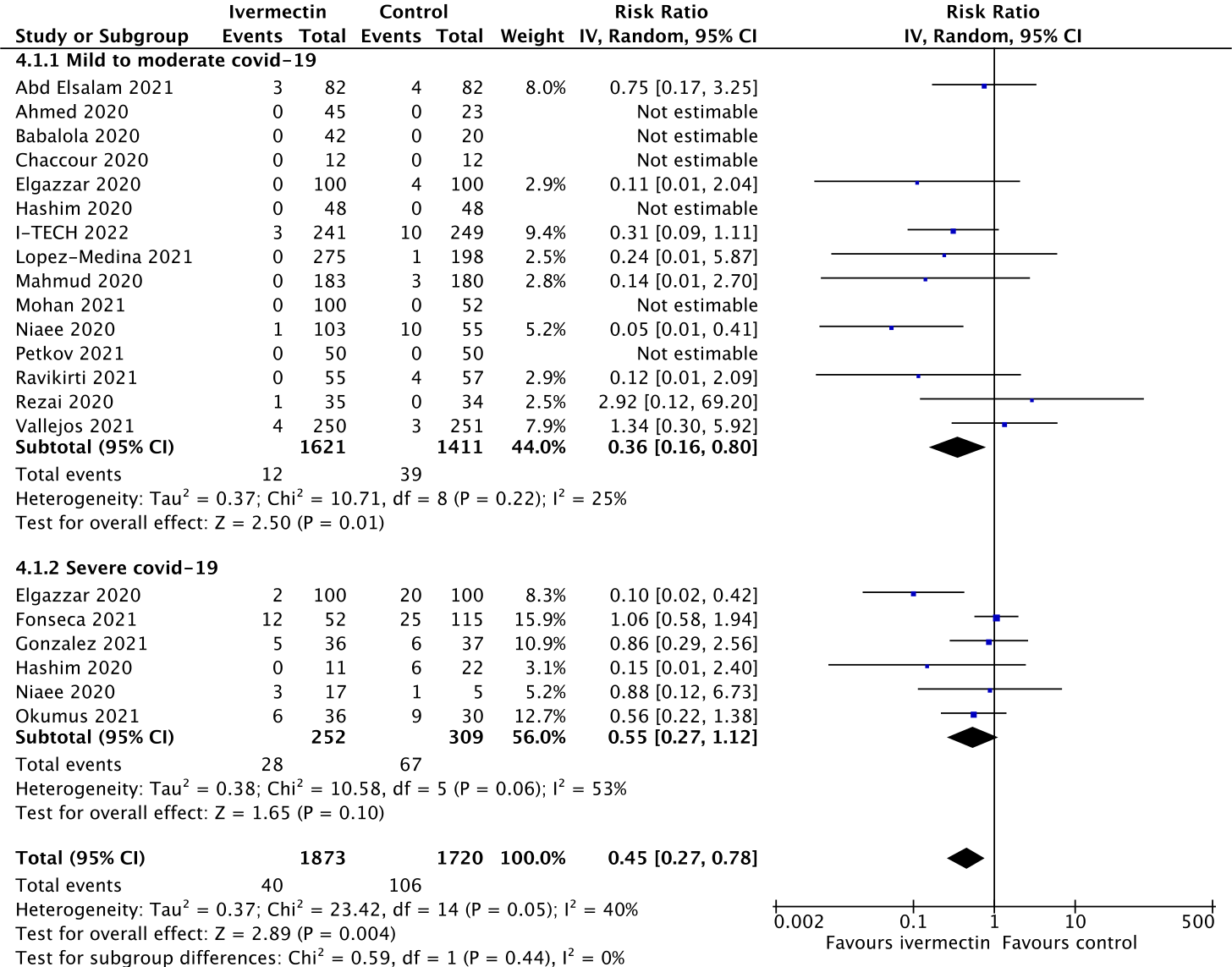

That’s what I and my colleagues did when we conducted our systematic review of ivermectin early last year. Below is the updated forest plot for ivermectin versus no ivermectin (the control) for mortality without the latest Together trial data (Figure 1). The overall estimate of effect of ivermectin on mortality suggests an average 55% reduction in deaths for the group that received ivermectin compared with those that did not. The square brackets next to the summary estimate of 0.45 indicate that most of the time the true estimate of effect lies somewhere between 22% and 73%.

Figure 1.

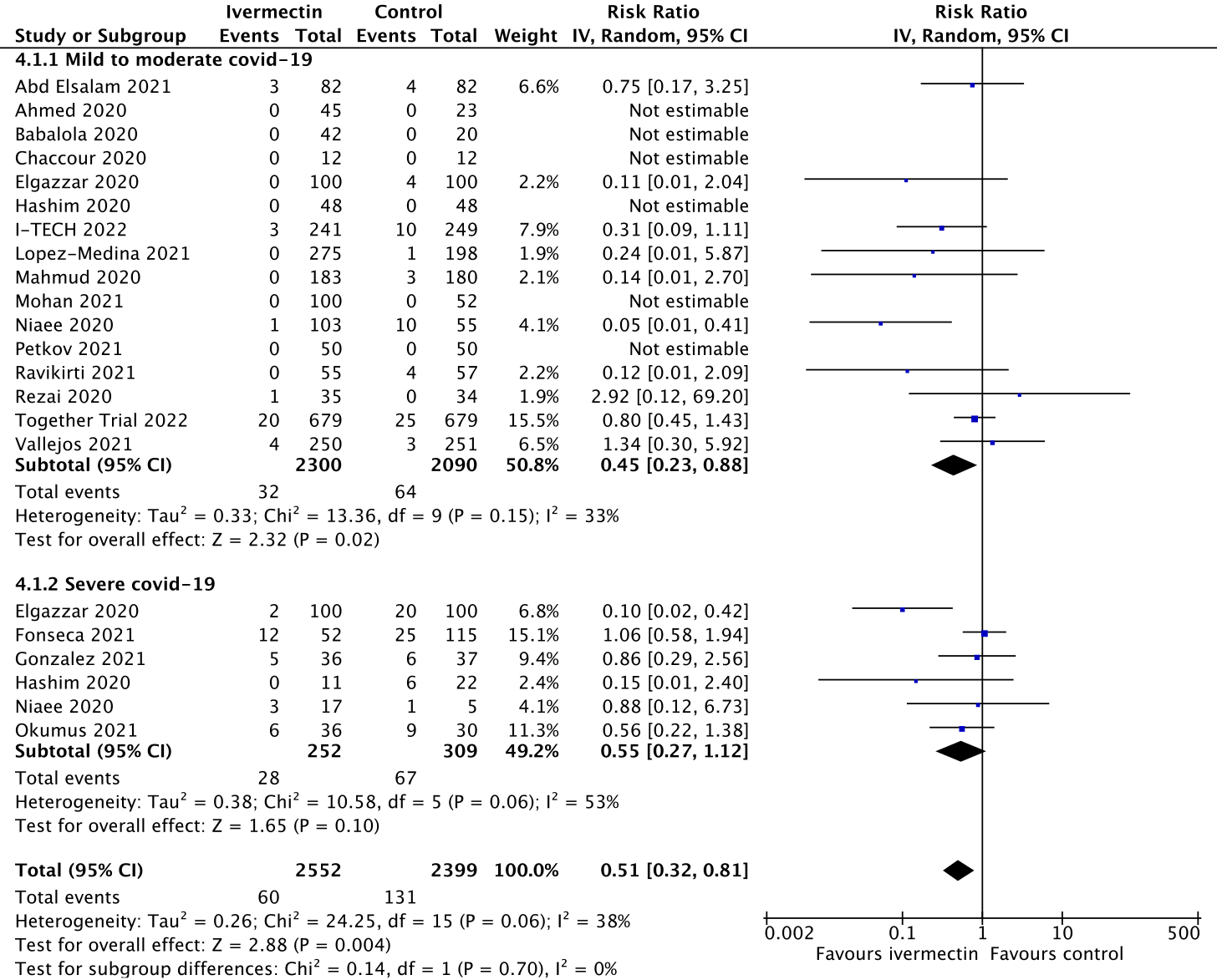

Figure 2 is the forest plot with the Together trial data added:

Figure 2.

This suggests an average reduction in deaths of 49% with ivermectin, showing that these new data are consistent with Figure 1 and that the Together trial data make little difference to the overall result. A measure of consistency is the I2 percentage, and you can see that with the Together trial added, the consistency remains more or less the same. I have given this trial the benefit of the doubt in terms of patient numbers and, therefore, the effect of ivermectin is likely to be underestimated, not over-estimated.

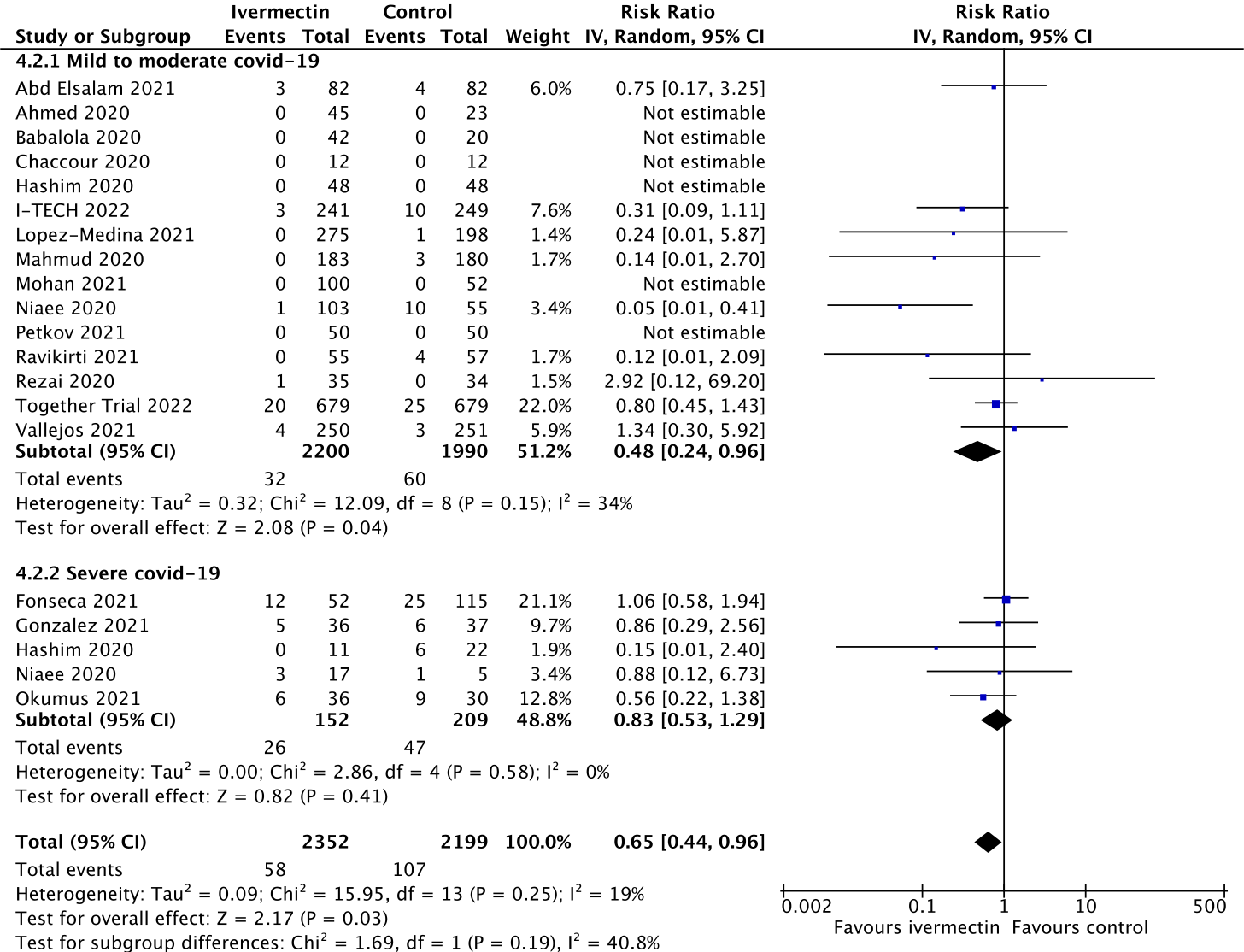

Some readers may be aware that questions have been raised by a student called Jack Lawrence about the Elgazzar trial from Egypt, so below you will find another forest plot with the Elgazzar trial data excluded for illustrative purposes.

Figure 3.

With Elgazzar excluded, the average reduction in deaths is estimated at 35% with ivermectin, again consistent with the original estimate of true effect lying between 22% and 73%.

It is important to recognise that few trials are perfect, and the Together trial is no exception. In fact, many red flags have been raised about Together’s study methods, conduct and conclusions by independent scientists, frontline doctors and journalists. These include questions about non-concurrent randomisation, non-identical placebos, poor adherence to the study protocol among the control group, and the administration of a single dose instead of ivermectin to a proportion. If adequate clarification is not provided by the trialists, this is likely to lead to calls for retraction of this paper.

The Covid situation, with its unique opportunity for large-scale pharmaceutical industry profiteering, has highlighted the fallibility of the randomised controlled trial study design: in essence, the design is open to manipulation in a variety of ways to produce desired results, both favourable or unfavourable. Cherry-picking trials based on perceived or known biases, whilst unknown or unquantifiable bias remains, is therefore quite dangerous and is in itself a form of serious bias in evidence quality assessment. This makes the role of the systematic review and meta-analysis more important than ever in the context of Covid, not least until sponsored trial data is both completely transparent and can be independently checked and verified.